Spiritual Notebook

Spiritual Notebook

Featured Article

A monthly insight into the spiritual life written by one of the monks of Belmont - A monthly insight into the spiritual life written by one of the monks of Belmont

Saints and Seasons

Reflections on the Saints of Belmont and homilies from the seasons of the year...

By Fr Brendan Thomas

•

19 Apr, 2020

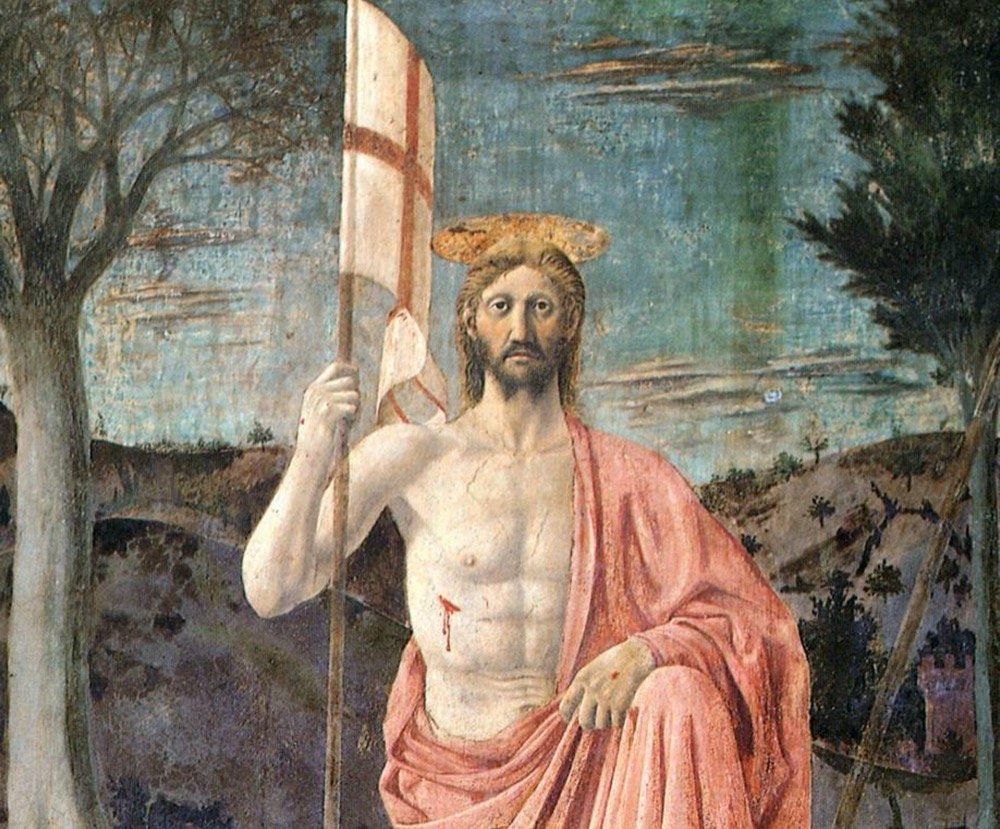

Writing in 1925 Aldous Huxley described a seven hour journey in an ‘omnibus’ to Sansepolcro, a small town in the less-visited eastern part of Tuscany: “And when at last one has arrived at San Sepolcro, what is there to be seen? A little town surrounded by walls, set in a broad flat valley between hills; some fine Renaissance palaces with pretty balconies of wrought iron; a not very interesting church, and finally, the best picture in the world… We need no imagination to help us figure forth its beauty; it stands there before us in entire and actual splendour, the greatest picture in the world.” The best picture in the world! That is quite a claim, but sometimes a painting can make an immediate impression. Piero della Francesca (1415-1492) was eminent in his lifetime as an artist, but surprisingly after his death was better remembered as a mathematician. Yet now he is considered the first true Renaissance painter who brought an original use of colour, light and perspective to his art. How do you paint the Resurrection? The Gospels contain no description of the actual event, only what happened afterwards. Any artistic depiction is going to be inadequate to the spiritual reality of what happened. “I saw Christ’s glory as he rose!” are the exuberant words put on the lips of Mary Magdalene in the Victimae Paschali Laudes (only she didn’t – she met him afterwards in the garden!) Piero portrays Christ as a colossus emerging from a Roman sarcophagus, victory won. The triumphant banner becomes his sceptre, the halo his crown. His dark piercing eyes convey his sovereignty. His wounds are still fresh and are on display for all to see. He has come through death into new life. We sing at Easter: “Death and life contended: combat strangely ended! Life’s own Champion, slain, yet lives to reign.” The Roman guards, in contrast to Christ’s strong form, sleep below, collapsed in a heap, oblivious to what is happening. Giorgio Vasari wrote that the soldier in brown armour was a self-portrait of Piero.

28 Mar, 2020

Tim Stanley, the historian and writer, gave a lovely Thought for the Day on Radio 4 on his affinity with St Cuthbert. He reflected on Cuthbert's love of solitude and concluded: “Monasteries might be set apart from society, but they are still deeply concerned with society. Monks work and teach, they carry out acts of charity, they pray for others, and they will be praying for the end of the corona virus right now… There is wisdom in a monk's desire to put aside the distractions of the world, the noise and the nonsense, and to focus on becoming a fuller human being by showing resilience and compassion. It is not impossible that some people come out of this changed for the better." Listen here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p087w4gp There is a lovely story of Cuthbert emerging from the North Sea after one of his long prayer vigils in the cold waters off Lindisfarne. Two otters followed him onto the sand, prostrated themselves and licked his feet to warm them. They then dried his feet with their fur.

By Dom Brendan Thomas

•

22 Mar, 2020

Not everyone finds St John’s Gospel to be an easy read, and I think one of the reasons is that so often in the lengthy conversations it records – like that of the Woman at the Well last week, or the story of the Man Born Blind this week – the people don’t seem to speak to each other, but across each other, or about each other. Sometimes Jesus seems to want to speak at a higher, metaphorical level, to lead us deeper, but his interlocutor is thinking of something very concrete, like the need of a bucket to draw water. Just as today – a story is told about physical blindness, but it addresses the issue of spiritual blindness. To look more closely at today’s Gospel I suggest we follow the theme not of sight but of speech. It is interesting to zoom out from the narrative and just notice the dialogue of the people as they relate to each other. Or rather, as they fail to relate: as they talk at cross-purposes, or don’t talk to each other at all. If you read it carefully you will notice how they fail to treat the Blind Man as a human being. He is, it seems, an outsider, a beggar, somehow defective and not worth listening to. They want to leave him that way, but only as Jesus draws him into his circle do things change. Everyone talks about him and no-one talks to him. The situation brings to mind that provocative title of the former radio programme ‘Does he take sugar?’ That phrase is a reminder that people sometimes find it hard to relate directly to people who they see as 'different', even when they want to be considerate, kind and helpful. We find it here in the way people treat the blind man, from the disciples unwitting neglect to the Pharisees calculated ill-will. At the beginning of the story the disciples talk about him but they do not speak to him. Then when he is cured the neighbours talk about him but they say nothing to him until he speaks out and says “I am the man.” Then he is taken to the Pharisees and again they begin by talking about him rather than to him. The Pharisees summon his parents, but they refuse to talk about him. They say he is of age, he will speak for himself. And he does so even more strongly culminating in his confession of faith: “Lord, I believe.” (It is beautiful to read this story in Lent with the Catechumens who will be led to the waters of Easter Baptism, as the man is sent to the Pool of Siloam) Jesus saw the Blind Man as he was: a human being, not an object. This is the story of a man finding his own voice. He ceases to be the object of conversation and becomes a subject. And more than that: by the end of the story he is able to say, not ‘I’ but ‘we’. He was made to belong. God’s creation is ultimately not of individuals but of a society, a community, a people. He was able to identify himself with others and belong. Isn’t that one of the most important things the Church or society can offer: belonging? At Easter the Catechumen is incorporated into the living, breathing community of Christ’s body. But we have a problem. Apart from my brethren and our organist I am speaking to an empty church. Many Parish Priests will be celebrating Mass this morning, and find that they have only themselves to address. There is a Greek word which occurs in today’s Gospel that we do not find in any other Gospel, or indeed in the whole of early Christian literature. The word is aposynagōgos (John 9:22) . It means “expelled from the synagogue.” The word “synagogue” is itself Greek for “gathering” or “community,” similar to our world “church.” No-one has been expelled from this Church, but the effect is something similar. The people, particularly our elderly, have been sent into isolation, the reverse of what is meant to happen. The Man Born Blind didn’t need the corona virus to experience social distancing. We have a challenge as a Christian community of waking up to this new reality where people find themselves isolated and socially-distanced. How do we hold people together? Today is Mothering Sunday, when millions of people should be seeing their mothers, kissing them embracing them, and millions of mothers should be rejoicing in the sight of their children. But it cannot be, because death is at the door and to love means we must show restraint. But we have to be creative, and encourage our Catholic communities to find other means to enkindle that sense of belonging. Humans need social congress. Thank goodness for the telephone and the internet that can be a way of keeping in touch and reminding people of our love and support. We need to find ways of connecting with each other without infecting each other. We see today that Jesus spoke directly to the man, while others talked about him. We can be reminded from him to speak directly to people in their isolation. Perhaps ‘social-distancing’ is misleading. We are forced to have physical distancing, but we cannot leave each other socially and spiritually isolated. The way of Jesus is to bring people from isolation into community. In this crisis we have to think of new and creative ways.

By Dom Brendan Thomas

•

21 Mar, 2020

We don’t think of St Benedict living at a time of crisis. The orderly way of life that Benedict presents in his Rule speaks of calm, order and peace. Anyone making their way up to the great monastery of Monte Cassino where Benedict died will find PAX, ‘peace’, in large letters above its door. Peace is a delicate thing, and peace is only to be found in a crown of thorns, found amongst the struggles. Peace is found in a world that is broken and afraid, in a world that is often dark and troubled. We don’t think of St Benedict living at a time of crisis, but he did. The first half of Benedict’s life was a time of relative prosperity, peace and good government, but all that came to a sudden end, and the last 15 years of his life were a time of war, destruction and hardship, with shortages of food and basic goods. There were two natural disasters that afflicted Benedict in his time. The first was a climate crisis, an extraordinary change of weather patterns. In 536 the sun disappeared for nearly a year behind a veil of dust, shining feebly with a strange blue light, not global warming but global cooling. There were volcanic eruptions, floods and earthquakes, crop failures and famine. Today we mark the death of St Benedict around 547, but he lived through a pandemic in his final years. The plague of Justinian from 541-42 is estimated to have killed 30 to 50 million people. (World Economic Forum estimate). St Benedict lived at a time of crisis, but his Rule helps us find a way through when an invisible enemy lies at its door. As Abbot, he strove to cure unhealthy ways (RB 2), apply the ointment of encouragement and the medicine of Divine Scripture (RB28). From the Rule his monastery seems clean and orderly. The brothers wash, the towels are washed, the utensils are washed and returned in good condition. Of the tools of the monastery he says that everything should be cared for: “Whoever fails to keep the things belonging to the monastery clean or treats them carelessly should be reproved.” What do those strong words mean for us, when we have each other’s health at stake at this time of crisis? Benedict talks about the proper amount of food and drink, and is concerned about any excess. As the temptation is to ‘panic buy’ we try to remember that resources are to be shared. He talks about times of shortage – he experienced it. When something is not available, he asks us not to grumble (RB40) Rather he asks his brethren to pull together when times are tough for they would all have to do a bit more to bring in the crops, and put food on the table (RB48). In contrast to some other rules of the time he shows genuine sympathy for the sick. He provides for a separate room for their care and as he recognizes in another context, isolation can be of benefit “lest one diseased sheep infect the whole flock” RB28. Benedict shows particular concern for the elderly, and gives them special consideration as we are asked to do. Concern for the order and cleanliness of the monastery, is but a reflection of his concern for the spiritual order of our lives, and the cleanliness of our souls. Each day we are reminded more forcefully of Benedict’s injunction to “keep death daily before our eyes” so that we are all a bit more attentive to what we do (RB4). In his Prologue he reminds us to live each day as best as we can, because this life does not go on forever. Our celebration on 21st March of the feast of St Benedict this year is a sad occasion. This is perhaps the first Mass since the monastery was founded where we have had to keep the doors locked. It is sad to begin a period of isolation on the feast of St Benedict, when joy is tinged with sadness that our parishioners and oblates, neighbours and friends and retreatants cannot join us around this altar. For St Benedict, as well as a place where we as brothers become a community, the altar is the place where the monastery meets the world where guests, pilgrims and the poor are gathered, and we become one in Christ. But the love of Christ, which St Benedict always put first, goes beyond human restrictions, and we remain united in Christ with those outside, the fearful and suffering and all those who are on the front-line of this crisis and who are love-in-action in our communities. May that love of Christ that casts out the fear be in the hearts of all at this time. Benedict was a saint whose wisdom guided the world through the dark ages and continues to offer us a ray of light with a teaching that points to Christ. The care, the love, the compassion he shows can guide us still as we learn to use these days of isolation well, bearing one another’s burdens of body or character with the greatest patience. St Gregory the Great tells us that his response to a pandemic was practical: Benedict issued food and olive oil to local people to make sure they were kept well. As we hear from St Paul in a reading for the feast of St Benedict: “Do not give up if trials come; and keep on praying. If any of the saints are in need you must share with them.” Romans 12:12-13 Crisis, or no crisis, we all remain one in the Body of Christ. We will carry on doing what we have been called to do: praying for Church and the world, not neglecting its needs but trying to put that love into practice. What St Benedict calls: putting nothing ever before the love of Christ.

By Dom Brendan Thomas

•

03 Feb, 2020

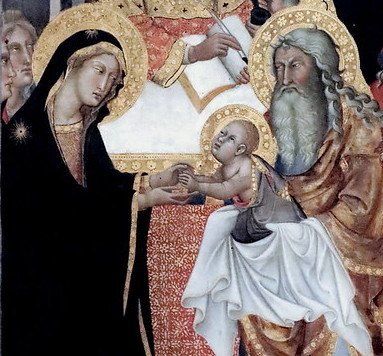

“Now, Lord, let your servant go in peace.” I love those two venerable figures Simeon and Anna and all that they represent. The faithfulness of old age. Simeon, content, happy, ready to let go, Anna, “whose days of girlhood were over” never left the Temple, which is probably no more than the biblical way of saying “she is always in church.” Always there lighting a candle. Expressing hope with her tired body by just being there day after day. St Pope John Paul dedicated this day to the Consecrated Life and some of our monks celebrate their profession today. But I think the feast of the Presentation should also be one when we give thanks for the dedication of our Elders, our Seniors, who are the backbone of many churches and never let the candles die out. If you are one of them, it is your special day too. Sigmund Freud, as I understand it, never wrote a line about aging, but Carl Jung had some lovely things to say about the latter stage of life. He described the first half of life as one of establishing ourselves and defining our proper place in the world, outwardly engaging with the world, achieving success at work, finding stability at home with a family. The second half of life should not be regarded as a time of decline (outwardly it might appear so!), but one of enrichment to develop our inner selves, find meaning, a new sense of purpose and a new understanding of ourselves. What is more, the spiritual task of the second half of life is different to that of the first. Changing oneself rather than changing the world. So he says “we cannot live the afternoon of life according to the programme of life’s morning – for what was great in the morning will be little at evening, and what in the morning was true will at evening have become a lie.” The child Jesus grew to maturity, and so must we, and spiritual growth continues to the very end. I think of Carl Jung’s words in relation to Simeon who in old age is able to embrace the mystery of Christ. He is ready to sing his Nunc Dimittis . He is ready to let go of all that has been and welcome something new. He found his meaning that day in the Temple, the object of his search, the longing of his people, the desire of the everlasting hills. And so all he can say is: Now, Lord, I am ready to go. We sing his words every night at Compline, as the day enters the night. As we say goodbye to the things that have passed it is almost as if we are in training for that final letting go. We have to learn to sing the Nunc Dimittis . Letting go of all that has been, the contentments and regrets, roads taken and not taken, and be reconciled with ourselves and with God. This week has been one of farewell, au revoir, adios, auf wiedersehen to the European Union. Its president Ursula von der Leyen quoted George Eliot: “Only in the agony of parting do we look into the depths of love.” Surely it is the hope of everyone that our departure is not a selfish turn, that it does not mean we become Little Britain, but that we rediscover our greatness in being a generous, big-hearted friend to our continental neighbours. The details of Simeon’s words are interesting because there is a surprise at the end of his little song. The salvation that God has “prepared for all the nations to see” is to be “a light of revelation for the gentiles and for the glory of Israel.” The novelty lies in the order: first a light for the gentiles, and only then for the glory of Israel.” To mention Israel after the Gentiles is to convey the sense that glory consists in having a role for others, not simply living for ourselves. Can Britain see beyond its self-interest of what it can get for itself, what we can get out of something? To repeat: glory consists in having a role for others, not simply living for ourselves. “My eyes have seen the Salvation” sings the just Israelite Simeon. The second half of life is also about seeing more deeply. We might say that if the first half of life is about law – engaging with the rules of life, the second half of life is about spirit – becoming free - going beyond the established boundaries. I love it that older people sometimes no longer care – in the best sense. They say what they think. They can say what is right. At that moment Anna comes round the corner and she can’t stop talking to everyone about the child – because like Simeon she has seen something too.

By Dom Brendan Thomas

•

01 Dec, 2019

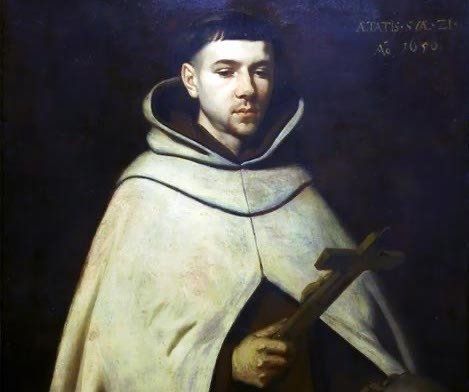

Darkness arrives increasingly earlier this time of year, shrinking our days bit by bit. The night is almost over, says St Paul. But still we are in a moment of darkness, This is our Advent. One of the loveliest, unexpected Advent voices is that of St John of the Cross, whose feast we will keep next week. The saint of the night, the saint of the dark night of the soul. In Advent of 1577, on the night of 2nd December, John was led bound and blindfolded to a monastery in Toledo where his own brothers imprisoned him. How Christians sometimes treat each other! The oldest Spanish landscape painting is one by El Greco, a contemporary of John. By chance El Greco depicts the priory in which John was held captive, just below the old Moslem Alcazar, high up on cliffs. He paints the city as a dark brooding presence at almost at the same moment in history as John was imprisoned within. They were dark days. There have always been dark days.

28 Mar, 2020

Tim Stanley, the historian and writer, gave a lovely Thought for the Day on Radio 4 on his affinity with St Cuthbert. He reflected on Cuthbert's love of solitude and concluded: “Monasteries might be set apart from society, but they are still deeply concerned with society. Monks work and teach, they carry out acts of charity, they pray for others, and they will be praying for the end of the corona virus right now… There is wisdom in a monk's desire to put aside the distractions of the world, the noise and the nonsense, and to focus on becoming a fuller human being by showing resilience and compassion. It is not impossible that some people come out of this changed for the better." Listen here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p087w4gp There is a lovely story of Cuthbert emerging from the North Sea after one of his long prayer vigils in the cold waters off Lindisfarne. Two otters followed him onto the sand, prostrated themselves and licked his feet to warm them. They then dried his feet with their fur.

By Abbot Paul Stonham

•

08 Mar, 2020

“It is time for the Lord to act, for your law has been broken.” With these words from Psalm 118, which we prayed at Office this morning, the Byzantine Liturgy begins, when the deacon invites the priest to give the opening blessing. They emphasise the fact that in the Eucharist, as in all the sacraments, it is the Lord who acts. They remind us, too, as we begin Lent today, that nothing will come of our penances, unless we allow the Lord to work his miracle of redemption in each one of us. This is why the prophet Joel writes, “Let your hearts be broken, not your garments. Turn to the Lord your God again, for he is all tenderness and compassion, slow to anger, rich in graciousness, ready to relent.” Lent is the time when we turn to God and ask him for his mercy and healing. ”Now is the favourable time; this is the day of salvation,” writes St Paul to the Corinthians. In fact, God is so merciful and loving that Paul can say, “For our sake God made the sinless one into sin, so that in him we might become the goodness of God.” Salvation doesn’t demand great sacrifices of us. God does not want us to undertake excessive penances during the forty days of Lent, but he does want us to open our hearts to him, so that he can do the rest. Salvation is God’s gift, not something we can earn or bring about by our own efforts. Holiness comes from our seeking God and allowing him to act in us. In today’s Gospel, Jesus warns us not to do things in order to attract the attention of others. Give arms, pray and fast by all means, but not like hypocrites, who want to be seen by others and praised for their good works. No, we are to do everything in secret; only God is to know what we are doing as we seek to follow Christ. Although it is an ancient custom to place ashes on our heads today, the keeping of Lent is something intimate between God and each one of us. Above all, unless we undergo a change of heart, a real conversion, the whole exercise will be pointless and to no avail. Yet ashes can be a reminder of what we should be aiming for. “Thy will be done,” Jesus taught his disciples to pray, and that is the goal of Lent. Now there are many penances and good works to choose from, but above all, God is calling us to accept his will and the penance he has already given us. It could be something to do with our character or weaknesses. It could be accepting someone we live with or something about them which we particularly dislike. As we grow older, it could be about accepting ill health, diminishment or loss of freedom. As we receive the ashes this morning, we will hear the words, “Remember that you are dust and to dust you shall return.” It would be good to reflect on these words of Scripture today. We are dust, dust and ashes, and yet dust and ashes that have been given new life through the Spirit of the living God. Passion, Death and Resurrection lie before us as we journey towards eternal life. Where Christ has gone, he will surely lead us, in spite of our many weaknesses and shortcomings. We are in his hands. “It is time for the Lord to act, for your law has been broken.” Amen.

By Dom Brendan Thomas

•

10 Feb, 2020

We have little biographical information about St Scholastica, except that she was always close to her beloved brother Benedict. They were twins – and so at birth they were united – and even in death they lay, and still lie together in a single tomb. Beyond that there is only one single episode in the life of Scholastica that we know, recorded by St Gregory the Great. It is short, slightly comic, but crucial moment. He says that when Scholastica was visited by her beloved brother, his stay was just not long enough. So she turned to God. Her powerful prayer forced the heavens open. The thunder came, so did the rain. Storm Scholastica. Bad weather forced Benedict to stay. It is a crucial episode in the life of that great legislator Benedict. Because it was a lesson about the relationship between law and love. All Benedict wanted to do was keep the law. "It is time to get back for Compline, Sister," he might have said. He knew the rules: he wrote the book. Surely that is all we need do? But Scholastica was rather naughty (in the painting she looks as if she has been up to something!). When the rain came pouring down Benedict was forced to put something very human, fraternal friendship and love, before the law. And St Gregory the Great tells us that Scholastica “proved more powerful because she loved more.” It was a simple lesson, but a profound one. God is not law. God is love. We do well to learn Scholastica’s lesson of love. +++ We prayed today especially for our Benedictine Sisters, particularly the houses of our own Congregation – Stanbrook, Colwich and Curzon Park and their communities. We prayed also for the Benedictine nuns in our parish at Howton Grove, Sr Catherine and Sr Lucy, our Oblates, and for all Benedictine and Cistercian women throughout the world.

By Abbot Paul Stonham

•

25 Dec, 2019

“From his fullness we have all received grace in return for grace, for grace and truth have come through Jesus Christ.” This morning we have come to thank God for the birth of his Son, our Saviour Jesus Christ, begotten of the Father before time began, born of the Virgin Mary by the power of the Holy Spirit, a man like us in all things but sin. We have prepared for Christmas by faithfully keeping Advent, the season of hope and consolation. We have heard the message of the prophets. We have prayed earnestly for his Coming and have longed to celebrate the feast of his Nativity, praying that he prepare in our hearts a crib in which to lie and so fill our lives with grace and truth. Today we see in the manger “the radiant light of God’s glory, the perfect copy of his nature.” That’s how the letter to the Hebrews puts it: he who “sustains the universe by his powerful command,” who having “destroyed sin, has gone to take his place in heaven at the Father’s right hand.” The new-born babe we kneel to adore is God made man: in the words of Charles Wesley’s hymn, “Veiled in flesh the Godhead see; hail the incarnate Deity, pleased as Man with man to dwell, Jesus our Emmanuel.” In Jesus, God is with us in a new and unexpected way. St Irenaeus wrote, "The Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He Himself is." God’s plan for us is far greater than we can hope for or imagine. It shatters our expectations. That God should become what we are in order that we might become what he is, shows us the unfathomable riches of God’s love. In the Incarnation, God opens his heart to us and Jesus reveals the truth about God: that He is love and that his love for us is absolute and unconditional. At this season, of course, with its cards and cribs, Nativity plays and carol services, not to mention excessive bouts of retail therapy, it’s easy to get sidetracked into a superficial haze about Christmas without any real theological or spiritual depth. This is not a criticism, for such things do contain elements of truth. The real poverty of the Child in the manger, for example, has little to do with the picturesque circumstances surrounding his birth. Rather it is the fact that this Child is God, God who lays aside his divinity to take upon himself the condition of humanity, the Lord who becomes a servant, the Creator who enters fully into the fragility of his creation and throughout his life on earth experiences the vulnerability and precariousness of human life, from being a foetus in his mother’s womb and a new-born baby in swaddling bands to being taken prisoner, tried, scourged and condemned to death, crucified and buried in a tomb. All this he did for love of us, to save us from hell; to reconcile us with himself and to open up for us the gates of the Kingdom of Heaven; to wrap us for ever in his embrace. Such is the loving mercy of God. In 2nd Corinthians St Paul writes, “Though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, so that by his poverty you might become rich.” This morning we join Mary and Joseph, the shepherds and the angels, indeed the whole of creation, in worshipping and adoring the Christ Child, recognizing him to be our God and Saviour, the Word through whom all things were made, the Light that darkness cannot overpower, the Source of grace and truth. To Him alone be glory and honour now and for ever. Amen. On behalf of Fr Prior and the Monastic Community, I wish you and your loved ones a very happy Christmas.

By the Belmont Webmaster

•

11 Oct, 2019

As we mark this coming year the 700th anniversary of the canonisation of St Thomas Cantilupe, Dean Michael Tavinor of Hereford Cathedral recounts his remarkable life and the respect and devotion he inspired. Most saints have to be content with one feast day! Several saints have two, but Hereford’s own St Thomas has a grand total of three! Born into a noble family, Thomas Cantilupe was a bright child and studied at Oxford and Paris. Entering the world of politics he became Chancellor to Edward I and, in 1275 was consecrated bishop of Hereford. From all accounts he was a faithful and hard-working pastor in this diocese. But he was feisty (he is said to have had red hair!) and he fell into an argument with John Pecham, archbishop of Canterbury about land rights in the diocese of Hereford. The dispute became so fierce that Pecham excommunicated Cantilupe – a terrible punishment, as it denied to the person so sentenced the benefits of Church and Sacrament, and worse still, denied any chance of bliss in the hereafter. Cantilupe, determined to clear his name set off in March 1282 to plead his cause with Pope Martin IV. With his entourage, he travelled from Hereford, via Paris, Nimes and Genoa, arriving at Montefiascone, near Orvieto in August. Here he is said to have been received well by the Pope and received absolution. But his health rapidly deteriorated – he contracted a fever and died on this day in 1282. His body was boiled, to remove the flesh from the bones – the flesh buried at the monastery of San Severo, outside Orvieto. Cantilupe’s heart was brought back to England and placed in the care of a college of canons at Ashridge in Hertfordshire, while his bones were brought back to Hereford, for interment in his cathedral. From the moment of his death, Richard Swinfield, Cantilupe’s successor, saw it as his duty to be responsible for his master’s body but also to drive a campaign for him to be canonised as one revered for his holiness. It was no easy task.

By the Belmont Webmaster

•

09 Oct, 2019

The Belmont Community were invited to begin the year of celebrations for St Thomas Cantilupe by singing Vespers at Hereford Cathedral. There was a very good crowd in attendance, and it was a lovely opportunity for Belmont parishioners to join the Cathedral community and guests that day. We were joined by a Catholic pilgrim group from South Shropshire led by Canon Jonathan Mitchell. St Thomas Cantilupe was Bishop of Hereford from 1275 until his death in 1282. His shrine is located in the north transept of Hereford Cathedral and is still an important pilgrimage destination. He also served as Chancellor of Oxford University and was involved in high-level politics as the Lord Chancellor of England. The celebration year runs from October 2019 to October 2020. It will include the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams leading a service of Reconciliation, and Lord Pattern of Barnes, the current Chancellor of Oxford University. Sir James MacMillan is composing two pieces of music to celebrate St Thomas. At the Vespers our new deacon Dom Augustine presided and Dean Michael preached about the significance of the relics of St Thomas. Together on the altar were the three main relics for the saint from Downside (his skull), Stonyhurst, and Belmont. Further details of the programme of events can be found below, with pictures from the day.

By Abbot Paul Stonham

•

24 Aug, 2019

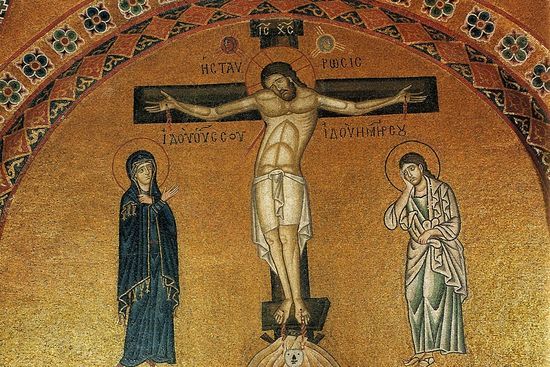

“Victory and power and empire for ever have been won by our God, and all authority for his Christ.” With these words the Book of Revelation celebrates God’s final victory over sin and death through the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. When we look at history and contemplate the state in our world today, coming face to face with the power of evil, these words seem pure fantasy. Yet our faith in God’s plan of salvation and the celebration of Our Lady’s Assumption allow more than a glimmer of light to shine through the darkness. Indeed, faith in the Resurrection has given Christians courage and hope in the most horrific situations the world has ever known. Think of St Maximilian Kolbe, whose martyrdom we celebrated yesterday. Not only does the Resurrection shed light on our doubts and fears, it also gives meaning to the mystery of Man. Only when Jesus rose from the dead did the disciples begin to understand the meaning of his life. Things fell into place. At last they could see the big picture, God’s scheme of things, the History of Salvation and our part in it. Just as every feast is a celebration of Easter and the Resurrection of Christ, so too the Assumption, for we believe that Mary, the Mother of God, was taken up body and soul into the glory of heaven. It is the greatest feast of Our Lady, from which all others spring, the matrix of Marian devotion. The Assumption came to be known as Little Easter or Easter in Summer and, in many parts of Europe, Catholics can make their Easter duty today. Through the power of the Holy Spirit, the Son of God took flesh and blood from Mary, and it is that flesh and blood, which were taken into heaven at his Ascension. In his Incarnation, God shared his divine life with us as in Mary’s womb we shared our humanity with him. That humanity entered the glory of heaven when the risen Christ ascended to the Father’s right hand. As a special privilege, as a foretaste of our common destiny, that flesh and blood entered into the glory of heaven a second time when Our Lady fell asleep and was assumed body and soul, such was the depth of her divine Son’s love for his Blessed Mother. An ancient antiphon declares, “Through Mary, the gate of heaven, you came to crown our hope and fulfilment: today she goes before us into your kingdom.” Today we heard these words of St Paul, “All men will be brought to life in Christ; Christ as the first-fruits and then, after the coming of Christ, those who belong to him. After that will come the end.” We belong to Christ through faith and baptism. We also belong to him through Mary, the glory of our race, the Mother of all who live and Queen of heaven. Today we celebrate the Easter Mystery, eternal life made manifest in Mary, the “lowly handmaid” of the Lord. “Yes, from this day forward all generations will call me blessed, for the Almighty has done great things for me.” The Magnificat is not only Mary’s song of praise and thanksgiving for what God has done in her. It is also a prophecy of what he will do in each one of us. “His mercy reaches out from age to age for those who fear him.” So, it is true. “Victory and power and empire for ever have been won by our God, and all authority for his Christ.” Christ is risen and Mary is assumed into heaven. Thanks be to God.

By Abbot Paul Stonham

•

10 Jun, 2019

“Do this as a memorial of me.” St Paul relates in First Corinthians that Jesus said these words at the Last Supper, both of the bread and of the cup: “This is my body, which is for you. This cup is the new covenant in my blood.” Paul himself adds, “Until the Lord comes, therefore, every time you eat this bread and drink this cup, you are proclaiming his death.” So it is that Jesus transforms a simple Passover meal into the heavenly Banquet, the Marriage Feast of the Lamb. That is what we do every time we gather together as God’s family to celebrate the Eucharist, the Sacrifice of the Mass. From the earliest days, the Christian Church, as recorded in the New Testament, our forebears in the faith believed without doubting the word spoken by the Lord and its power to bring about what it says, just as at the beginning of creation God had said, “Let there be light”, and there was light. This is the faith of the Church today, our faith. When Jesus says this morning, “This is my body, which is given for you,” and “This is the cup of my blood, which is shed for you,” we can be sure that his word is true and that what he says, he does. However, it is not only in the Real Presence that Christians believe, for Jesus asks us to “do this as a memorial of me”. The Mass is a memorial of the whole of Christ’s life, from his Conception through the working of the Holy Spirit to his Ascension and the outpouring of that same Spirit. In other words, the Mass makes present for us the whole Christ event and, what is more, anticipates and prays for his Coming in glory as Judge at the end of time. When we talk about the Sacrifice of the Mass, we naturally think of Christ’s Passion, Crucifixion and Death, and, of course, in the Mass we are totally immersed in the Cross of Jesus, but it is true to say his whole life is sacrificial. In the Mass, then, we celebrate the whole of the Mystery of the Incarnation: his Conception in the Virgin’s womb, his Nativity in the cave of Bethlehem and his lying in the manger, his Circumcision and first shedding of the Precious Blood for our redemption, and so on. Every moment and aspect of the life of Jesus is Sacrifice, including his Resurrection. At Mass, in the Son, we receive the Father and the Holy Spirit. God, though three persons, is but One, and in communion with Christ we are united to the Holy Trinity. But there is something more. In today’s Gospel we read St Luke’s simplified account of the feeding of the five thousand. There was no small boy to bring forward the five loaves and two fish, one of the loveliest images in the Gospels. Even so, with this inadequate offering, Jesus is able to feed the multitude and there are leftovers in abundance, enough to fill twelve baskets. Leaving aside numerical symbolism, with the humblest of gifts, Jesus is able to feed a vast number of people and there is a lot left to share with others. Like the manna in the wilderness, the food, with which Jesus feeds us, does not run out. He who created all that is, can feed the hungry and nourish our souls. However, as with the widow’s mite, he needs the little we can give, especially if it is given with a loving and generous heart. At Mass we offer him bread and wine and receive in return his Body and Blood. What an extraordinary exchange of gifts! That is why we have come together to give thanks.

By Abbot Paul Stonham

•

21 Apr, 2019

“When the women returned from the tomb, they told all this to the Eleven and to the others, but this story of theirs seemed pure nonsense, and they did not believe.” “Pure nonsense” is what we’re celebrating tonight. The apostles and the other disciples found the news of the empty tomb and the message of the angels to the women, that the Lord Jesus had risen from the dead, simply impossible to believe, in fact, “pure nonsense”. No doubt, we would have reacted in the same way. So it shouldn’t surprise us today when we read and hear all sorts of wild interpretations about Jesus, the Resurrection, the Gospel, the Christian faith and the Church. It was the same at the beginning, starting with the scribes and Pharisees. As for the disciples, it wasn’t the news they were expecting or hoping for and they couldn’t understand what was happening. They were being asked to believe the impossible. We learn by making mistakes and reflecting on personal experience. The same happened with the apostles. What the angels had told the women slowly began to sink in. “Why look among the dead for one who is alive? He is not here: he is risen. Remember what he told you; that the Son of Man had to be handed over into the power of sinful men and be crucified, and rise again on the third day.” Pure nonsense or not, they had better go and see for themselves what on earth was going on. Think of the reaction of Thomas, when the others told him something similar to what the women are saying tonight, “Unless I see the holes in his hands and can put my fingers into the holes and unless I can put my hand into his side, I refuse to believe.” So, early in the morning on the first day of the week, something finally twigged in Peter’s mind. Hadn’t he heard Jesus talk about this very moment many times? He went running to the tomb and, finding it empty, came back, amazed at what he had seen. His doubts began to evaporate in the first light of dawn. He was beginning to believe: he was beginning to see the light. Only gradually, as Jesus appeared first to one, then to another, then finally to all of them, did the disciples come to believe that he had truly risen from the dead. Even so, remember what Jesus said to Thomas, “Blessed are they who have not seen and yet believe.” We give thanks to God for the gift of faith. It might still be “pure nonsense” for many, but for us Christians the Resurrection of Jesus is the source of our joy. It is the key that opens the door to understanding life and death and, ultimately, God’s plan for his creation. In the Resurrection we see the light of truth. St Paul, writing to the Romans, gives us this interpretation of the Paschal mystery, “When we were baptised, we went into the tomb with Christ Jesus, so that as Christ was raised from the dead by the Father’s glory, we too might live a new life. When he died, he died to sin once for all, so his life in now life with God. So you too must consider yourselves to be dead to sin, but alive for God in Christ Jesus.”

By Abbot Paul Stonham

•

19 Apr, 2019

“It is not as if we had a high priest who was incapable of feeling our weaknesses with us. Let us be confident, then, in approaching the throne of grace, that we shall have mercy from him and find grace when we are in need of help.” These words from the Letter to the Hebrews sum up the message of the Gospel and the essential truth of the Christian faith. They place the reality of our lives in the context of God’s plan for our salvation. When we consider the extent of human suffering, it’s not easy to believe in a loving God, a God who wants life and not death. Even when our faith is strong, we struggle to believe. It’s not easy to accept a God who can allow so much suffering. The story of Christ’s Passion is one of pain and rejection, of physical and spiritual anguish. It doesn’t explain or take away suffering or its causes, but it does say something very important about God. In the Mystery of the Incarnation, God enters into our world to share fully the tragedy of human life. Julian of Norwich writes of a conversation she once had with the Lord Jesus, which sheds light on the interplay between our suffering and sin and the Passion of Christ. “Our good Lord Jesus Christ said, ‘Are you well satisfied with my suffering for you?’ ‘Yes, thank you, good Lord,’ I replied. ‘Yes, good Lord, bless you.’ And the kind Lord Jesus said, ‘If you are satisfied, I am satisfied too. It gives me greater happiness and joy and, indeed, eternal delight ever to have suffered for you. If I could possibly have suffered more, I would have done so.’ And here I saw that the love, which made him suffer, is as much greater than his pain as heaven is greater than earth. It was because of this love he said, ‘If I could possibly have suffered more, I would have done so.’” Christ suffered and died for love of us all. St Catherine of Siena says, “Nails were not enough to hold God-and-man fastened to the cross, had not love held him there.” No one suffers alone, for whatever form our sufferings take, God is with us and, in Christ, God suffers with us. Again in the Letter to the Hebrews we read, “It is not as if we had a high priest who was incapable of feeling our sufferings. During his life on earth, he offered prayer and entreaty, aloud and in silent tears, to the one who had the power to save him out of death, and he submitted so humbly that his prayer was heard. Even so, it is in suffering that, although he was Son, he learnt to obey.” It is only in suffering that we come to see and know the living God. He is in our wounds, the open wounds of our suffering and pain, the wounds of the Risen Christ. The prophet Isaiah said, “Ours were the sufferings he bore, ours the sorrows he carried. He was pierced through for our faults, crushed for our sins. On him lies a punishment that brings us peace, and through his wounds we are healed.” On Easter night, in the Upper Room, Jesus greets his disciples saying, “Peace be with you,” then shows them his hands and his side, the hands that had been nailed to the cross, the side the soldier’s lance had pierced and from which had come forth blood and water. The wounds of Christ will remain open until the Last Day when he, the victor over sin and death, will hand over to his Father the whole of creation redeemed in his blood and renewed by the Holy Spirit. As members of the Body of Christ, we play our part in the work of redemption. Suffering is not futile. All suffering is redemptive and leads to salvation, all suffering has meaning and purpose and is a channel of grace, if we see God in the suffering, in the horror and the pain. Last night we sang, “We must glory in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ; he is our salvation, our life and resurrection.” Today we sing, “This is the wood of the cross, on which hung the Saviour of the world.” May God in his mercy help us grow in faith so that we really experience in our sufferings the Cross and Resurrection of Jesus. Amen.

From the Bird's nest in the cloister

Dom David Bird offers a monthly reflection from his experiences at Belmont and in Peru

By Father David Bird OSB

•

06 Jul, 2018

Fr David Bird returned to the UK after serving for a record 36 years in Peru. During those years he served as Assistant Pastor in Tambogrande, followed by three long stints as Parish Priest in Piura, Negritos and San Miguel de Pallaques in northern Peru, and finally as Superior of the Monastery of the Incarnation at Pachacamac. It has been very hard to pull himself away from the Community and the many friends and parishioners he got to know over the years. Fr David who is now 81 is already taking a full part in community life, leading some retreats and doing some teaching in the monastery. He is a fine theologian and runs an excellent blog called "Monks and Mermaids." It's well worth a visit: you might become an addict.

By Father David Bird OSB

•

24 Jun, 2018

Once upon a time, there was a nasty character called “Reprobus” (as in the word “reprobate”). In the Orthodox East he is remembered as a monster, and his icon shows him with the head of a dog. In the Catholic West, they say that he was a giant; and we all know that giants are only partly human, being the product of illicit sexual activity between angels of doubtful morality and human women (Gen. 6, 4). Reprobus was so nasty that he became an intimate friend and companion of the devil himself and he served him because he believed Satan to be the most powerful king in the world. Rebrobus was a soldier who went about doing harm. One day, he was travelling with the devil when he came across a wayside cross. To his astonishment, the devil showed obvious signs of distress and fear. It became clear to Reprobus that whoever was represented by this cross was more powerful than the devil. He left the devil’s service and began to look for whoever it was with a cross as his badge. It was not long before he met up with Christians, but his difficulties were just beginning. They showed no sign of worldly power, which was the only kind he knew. They were being persecuted in many places and were very peaceful and humble wherever they were, putting themselves out for people in need, more ready to serve than to dominate, the very opposite to his own behaviour. Moreover, this had something to do with the cross that put so much fear into the devil. He heard the Gospel and this made him want to become a Christian. Reprobus encountered two enormous obstacles, the first in himself, the second among the very Christians he wanted to join. He discovered that he could neither pray nor fast - two of the principal Christian activities. The second obstacle was that the Christians would not accept him. Who has ever heard of baptising a monster? How is it possible to baptise a giant who isn’t really fully human? Reprobus felt despair. He wandered the countryside, not knowing what to do. One day, by God’s providence, he came to a hermit’s hut and poured out his problems to the hermit that lived there. At that time, hermits were often the nearest thing to prophets, and this hermit was particularly wise and filled with the Spirit. “You tell me that you can neither pray nor fast, and that, because you are a monster (or a giant), the Church refuses to baptise you. If those doors are shut to you, you must enter through a door that is open. “Anyone who wishes to visit the town must cross a river which is deep and dangerous, and many in bad weather have died trying to cross. You can serve the good Lord by living on its banks, helping people to cross, even carrying them on your shoulders if needs be. Perhaps Christ will accept this service instead of those you cannot accomplish at present.” This is what Reprobus did. He built himself a little hut by the river and accepted the task of helping people to cross. Little by little, he became a welcome sight for the people, especially when the river was dangerous. They began not to notice so much that he was a monster (or a giant). One day, when the river was particularly dangerous and he had had to make the crossing many times, he was just about to take a well-earned rest when a little boy entered his hut. “Would you please take me across. I am sorry I am late,” said the little boy. The coldness of the water cried out to him not to go. His tired limbs begged him not to go. The rain outside his nice warm hut called him not to go. But he looked into the little boy’s pleading eyes and he knew he must. Swinging the boy onto his shoulders, he stepped out into the cold and dark, climbed down the slippery river bank and began the crossing. The further in he went, the heavier became the little boy on his shoulders until even his monstrous strength was not strong enough and he began to falter. “I can’t make it!” he gasped. “Yes you can,” said the child. In what seemed like ages later, he made it to the other bank. Swinging the little boy down, he said, “How can a little boy be so heavy, me being a monster and all that.” The little boy smiled sweetly, “You had a little boy on your back and I had the whole world on mine, you didn’t do so badly.” The little boy then revealed himself to be Christ, and he instructed the monster (or giant) to go and tell the bishop. “Tell him to baptise you with a new name. From now on, you shall be called, “Christopher” “Christ-bearer.” Then the child vanished. Christopher gained a reputation for holiness among Christians and was a cause of many conversions to the faith. He was later martyred for the same faith by de-capitation. I have called this “The true Story of St Christopher” not because it literally happened, but because it tells the truth, whether it actually happened or not. One of the most distorting things that has happened is dividing Catholics into “progressives” and ”conservatives” The St Christopher story is Catholic and has characteristics of both. Like “progressives”, it urges universal tolerance in accepting all, even the most way out. Like “conservatives”, it tells us that sin really is an obstacle to our relationship with God and insists on real readiness to change as far as they can on those whom the Church accepts, and trusts the grace of Christ to do the rest. Reprobus started off as a monster and ended up a martyr. The story assumes that Christ is the Good Shepherd who leaves the 99 to find those that are lost, not letting rules, however important, to stand in his way. Fr David is monk of Belmont who spent 36 years in Peru and has a particular interest in the church East and West. His other blog is 'Monks and Mermaids'.

Unfolding the Word

“The Unfolding of your

Word gives light.” says the Psalm.

Each week Dom Alistair reflects on the readings for Sundays and Solemnities, which can be used for a weekly Lectio Divina.

Our Monastery

Belmont AbbeyRuckhall LaneHerefordHR2 9RZ

Phone: 01432 374710E-mail:

Enquirieswww.belmontabbey.org.uk

HOW TO FIND US

Copyright 2018 © Belmont Abbey. All rights reserved | “Belmont Abbey General CIO (registered charity number 1190035).

Principal office: Belmont Abbey, Ruckall lane, Hereford HR2 9RZ.”

Principal office: Belmont Abbey, Ruckall lane, Hereford HR2 9RZ.”

Website developed by:

Every Day Christian Marketing Ltd